Location: Foyles, London

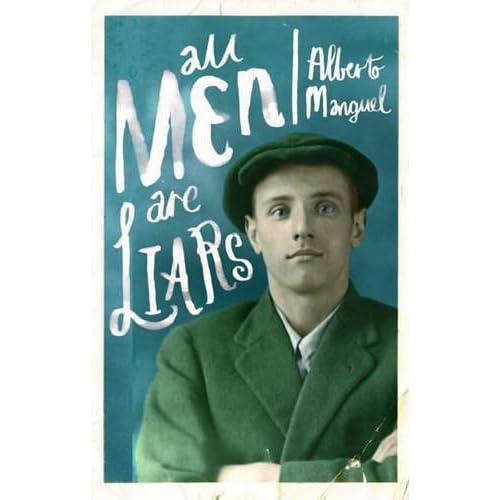

All men are liars, but you can't take that statement as the absolute truth. As Alberto Manguel says, inside the cover of the book, you can read the whole phrase from Psalms: 'I say in haste, all men are liars...'

It is not in haste, however, that I say I had a thoroughly enjoyable evening listening to Alberto speak with Maya. I felt so alive leaving the event, mainly because I love metafictional discussions, and though Alberto never used that word, he is all about metafiction. After all, he is the disciple of Borges ... but I'm sure Manguel was tired of discussing his relationship with Borges, so likewise, I'll talk about him last.

W

here to start, really? I first learned about Manguel when my father brought home a copy of this; he extolled about how trail-blazing Manguel was in being one of the first academics to write about the history of the act of reading. Nobody really paid serious attention to the phenomenon of reading as a cultural act until Manguel stepped into the scene. Well anyway, like the good daughter that I was, I didn't touch the book until it was assigned in an undergraduate course on Readers and Readership. It is an amazing book, very well-researched, and it makes you navel-gaze and examine yourself as a reader.

here to start, really? I first learned about Manguel when my father brought home a copy of this; he extolled about how trail-blazing Manguel was in being one of the first academics to write about the history of the act of reading. Nobody really paid serious attention to the phenomenon of reading as a cultural act until Manguel stepped into the scene. Well anyway, like the good daughter that I was, I didn't touch the book until it was assigned in an undergraduate course on Readers and Readership. It is an amazing book, very well-researched, and it makes you navel-gaze and examine yourself as a reader.Anyway, the interviewer Maya Jaggi introduced him with a quote: 'Alberto Manguel is to reading what Casanova is to sex'. Ha. But I can confirm, he can make you get literally excited over books! He read aloud his latest novel, All Men Are Liars, and the novel sounded very intriguing indeed. He wrote it in Spanish even though he originally wanted to write it in English (he is Argentinian-Canadian, but his first language is English). He said that earlier on, he wanted to set the story in Canada, but found that Canadians are too nice (ha!) and had to move the story to Spain.

The metafictional bit is that in the story, he includes himself as a character, but he is the first to admit that Alberto Manguel the character 'is an asshole'. An audience member asked why he wanted to write himself into the book if he doesn't identify with the character much. His response reminded me of his earlier book ... in that he explained the act of telling a story is age old, harking back to cavemen sitting around campfires. People would enter into an unspoken agreement that whatever you say happened to you is to be taken as the truth, and that the listener will strive to believe you in the duration of your oral narrative. More than that, he says he believes that fiction/literature is the way to the truth. Though it hovers between lies and truths, 'literature has the last word ... I always trust in literature', but it takes time for books to be written. It takes time for events to settle down, for a writer to capture the sign of the times, time to train the readers to accept the stories and enjoy them and think about them. As he said, Joyce wasn't an instant bestseller. It took a lot of years to 'educate' readers to appreciate, say, Ulysses. (He then goes on to criticise the Anglo-publishing industry's obsession with churning out bestsellers instead of well-written novels...)

All Men Are Liars is a genre book of sorts, in the style of detective novels, as it presents different versions of the same character or event. Manguel points out that actually this style is not new. It is very old: you can also find it in the Gospels. How true! I never thought of it that way, that reading the Gospels is kinda like reading a detective novel where you try to piece the 'truth' of an event together (in the case of the Gospels, it is to piece together what really happened to Jesus, figuring out how reliable the different accounts are, etc).

All Men Are Liars is a genre book of sorts, in the style of detective novels, as it presents different versions of the same character or event. Manguel points out that actually this style is not new. It is very old: you can also find it in the Gospels. How true! I never thought of it that way, that reading the Gospels is kinda like reading a detective novel where you try to piece the 'truth' of an event together (in the case of the Gospels, it is to piece together what really happened to Jesus, figuring out how reliable the different accounts are, etc).Alberto goes on to talk about spies and informers ... how he is obsessed with how one can access the 'truth' about someone, or something ... when everyone can have different interpretations to the same person/event. He explained that this is because he was brought up in a good school in Buenos Aires, and he had an amazing teacher who opened up his mind to reading, and taught him that books can do wonders to your way of thinking ... but after he escaped from the years of the Dirty Wars (and lived in 'exile' ...) he found out that this very same teacher turned into an informer during the dictatorship period. He would report on his students' behaviours and was complicit in torture. How does one reconcile the two faces of the same man? Manguel says that he can do so through literature.

... and this leads naturally to his comment on Borges. Maya asked Alberto if he cares to speak about his relationship with Borges, the father of all modern literature. Manguel seemed slightly weary of the topic, but he was a good sport and gave what the audience wanted. After all, he met Borges as a teenager, and read aloud to him (Borges was near-blind). It was amazing hearing from someone who had first degree contact with Borges. Anyway, Manguel explained that whatever you want to write, Borges would have already written it.

Borges pointed out things that no one else had verbalised before until he did: that, for example, context matters a lot. That writing Don Quixote word for word now would create a totally different text to the Don Quixote written in Cervantes' time (as seen in 'Pierre Menard'). I know it's obvious now that context can be a very important thing to the interpretation and reception of a text, but actually it is quite a new phenomenon in the history of cultural criticism. That is, until Borges came along.

And the most amazing of all ideas, the reason why I love Borges so much: it is the fact that in real life, things can be quite black and white, but in literature, liminality and paradoxes occur. Manguel says: 'dogma gives you answers, but literature gives you questions'. How can you reconcile different types of truths? How can you believe Betty's version of something over Don's, for example? Maybe they are both correct? Literature can make you want to question deeply about things that you accept as truths .. make you dream about an alternate reality where impossible things can become possible. It then can motivate you to want to turn these impossible things into real things in real life (in other words, literature can incite change, politically and psychologically). Anyway, Manguel's example of how Borges illustrated this concept is through his reading of Dante's Inferno. If you have studied the Inferno in class, you would know that every Dante scholar loves to argue about the grotesque episode of Ugolino: since Dante doesn't say explicitly, scholars would argue over whether Ugolino's presented as having eaten his children or not. Ugolino was a real person in history, and so, Borges pointed out: in real life, either Ugolino ate his children or he did not. But in literature, he ate his children and he did not.

You probably think I'm sounding like a literary lunatic, but really, the most beautiful ability in the world is to hold two disparate, opposite thoughts at once, and not find that problematic. If you agree with me, then you will enjoy reading 'The Garden of Forking Paths'. I challenge you to read it and not have your mind blown away by Borges' short story.

I just realised I digressed into Borges. Oops. Alberto Manguel is an amazing individual! It was a wonderful hour of discussion, which reminds me: I will read his new novel, once I finish the pile of unread books in my room ...

No comments:

Post a Comment